|

New Mexico - Route 66

New Mexico Road Segments

As it moves across the State of New Mexico, U.S. Highway 66 generally follows the region’s traditional east-west transportation corridor through the center of the State along the 35th Parallel. The topography of this route had always presented special challenges to New Mexican road builders even before the coming of Route 66 in 1926. New Mexico’s elevation along this path varies from a low of 3,800 feet at the Texas border to over 7,200 feet at the Continental Divide near Thoreau, creating a roadbed characterized by climbs, descents, switchbacks and cuts. These topographical conditions were especially daunting considering that until the 1930s, much of the road construction was done by human and animal muscle. The Big Cut north of Albuquerque and the La Bajada Hill switchbacks south of Santa Fe are testaments to these challenges--and achievements--of early road building in New Mexico.

Despite considerable progress after achieving statehood in 1912, New Mexico could boast of only 28 miles of hardened pavement. The rest of the roads had surfaces of gravel, rock or unimproved dirt. In addition, many of the bridges along New Mexico’s roads at this time were constructed of untreated timber or creosote coated timber. These less than modern conditions did not stem the increasing traffic flow across the State during the first years of Route 66. The mid-1920s witnessed the convergence of powerful social and economic trends that set the nation in motion as never before. The creation of Route 66 and a Federal highway system in 1926 coincided with the beginning of widespread automobile ownership and the rise of automobile tourism. Aided by private and civic booster organizations alert to these trends, the sparsely populated but visually stunning New Mexico became a major beneficiary of these developments.

New Mexico Route 66 became fully modernized during the Great Depression, as the Federal Government undertook massive public spending programs, many of which concentrated on road building. Between 1933 and 1941, New Mexico was a major recipient of these funds. Starting with the National Recovery Act of 1933, which allotted the State nearly six million dollars for road work, New Mexico received millions of Federal dollars throughout the 1930s and early 1940s for road construction and modernization projects that included new bridges, paving, grade crossing elimination, and roadway straightening.

In the midst of these New Deal efforts, the year 1937 stands out as a milestone in the history of Route 66 in New Mexico. In that year, New Mexico's section of the highway was significantly shortened and straightened by eliminating the major exception to the State’s east-west course: a giant S shaped detour in the center of the State that ran northwest from the eastern town of Santa Rosa to Romeoville and Santa Fe, and then south (through Albuquerque) to Los Lunas. At that point, the road turned once again in a northwesterly direction toward Laguna Pueblo, where it finally resumed its western direction. The new alignment shortened the road, reducing Route 66’s total New Mexican mileage from 506 to 399 miles, and routed the highway directly on an east-west axis through Albuquerque and its famous Central Avenue. By the end of 1937, the paving of Route 66 throughout the entire State was complete, making Route 66 New Mexico’s first fully paved highway.

The spending priorities and civilian travel restrictions of the Second World War cut short the economic upswing that emerged in the wake of the New Deal improvements. The postwar explosion in travel and transport, which launched Route 66 into its golden age, proved a double-edged sword. Despite heroic attempts to keep abreast of the surging traffic flow of the 1950s through road widening and new alignments, the Mother Road’s days as a national highway were numbered.

The Road Segments

The historic road segments described below follow Route 66 east-to-west through the State of New Mexico. Together, they illustrate the history New Mexico and Route 66 share. Some are still in use today. The man-made structures and natural wonders continue to draw travelers along the route.

Glenrio to San Jon

Extending from the Texas border at Glenrio to two miles east of San Jon, this 14.6 mile segment of Route 66 runs almost two miles south of Interstate 40 through the sites of the early homestead towns that lined the now abandoned Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. This departure from the interstate enhances the feeling of cross-country travel in rural eastern New Mexico, especially with the vistas across the slightly rolling semi-arid rangeland, the barbed wire fencing paralleling the road, and the remains of the railroad grade with its wood trestle bridges. While the segment has little elevation change, several small streams near Endee mark a visible change in the area’s topography. These streams made the area attractive to homesteaders but posed challenges for early road builders who used several stream crossings to pass through the area. When the road became part of Route 66 in 1930, road builders realigned it to eliminate stream crossings and run parallel to the railroad lying to the south. Engineers raised the grade and added several concrete culverts, often marked by short guardrails consisting of wood posts and connecting steel cables. Notable along this segment are four creosote-treated beam bridges east of Endee built during the 1930 alignment. These structures characterize bridge building over many of the flood plains and shallow riverbeds of the State in the 1920s and early 1930s. The cross sections of the early roadbed and the bridges remain largely unaltered. When the road was turned over to Quay County, it was given a gravel surface that enhanced its historic feeling and recalled the era of Route 66 that preceded its paving in the 1930s. This segment served as Route 66 until 1952.

San Jon to Tucumcari

Running across the rangelands and irrigated farmlands of eastern Quay County, this 23.9-mile segment is largely unaltered beyond normal road maintenance. The segment generally follows what was known as the Ozark Trail, a regional trail association that preceded the creation of the Federal highway system in 1926. The roadbed was paved with a hard surface in 1933. Traveling west, the road section passes through San Jon where commercial buildings, many now vacant, recall earlier roadside businesses that Route 66 travelers supported. In the distance, to the south and west, the Caprock and Mount Tucumcari offer views of the increasingly rugged terrain awaiting the westbound motorist. West of San Jon, the road diverges from Interstate 40 crossing rangeland well removed from the modern highway. Concrete box culverts and fill carry the road across small arroyos. Sandstone outcroppings mark the drainage of Plaza Largo and Revuelto Creeks with the pre-1933 alignment of the road visible 50 yards to the south. West of the drainage the road parallels the interstate, coursing beneath two overpasses. As the road approaches Tucumcari, canals and irrigated fields marking the Arch Hurley Irrigation District lie to the south.

Palomas to Montoya

This 10.4-mile road segment passes through the Parajito Creek Valley with Mesa Rica to the north and Palomas Mesa to the south. Remaining relatively flat at 4,300 feet, the road has a few bank or slope cuts along this stretch. Several sections, however, are marked by raised grades with culverts and bridges permitting water from small intermittent streams to flow into Parajito Creek just to the south. This road section was realigned from an earlier course in 1933. Of particular interest are the road’s three bridges consisting of reinforced concrete beam construction with concrete abutments. As the road approaches Montoya, it passes a series of vacant businesses and the Montoya Cemetery. This improvement is a good example of the Bureau of Roads’ staged construction policy and illustrates the changes New Deal road building projects brought to Route 66. This segment served as Routes 66 and 54 until the coming of Interstate 40 following the Interstate Highway Act of 1956. Works Project Administration project number plates are affixed to their headwalls.

Montoya to Cuervo

This 20.3-mile segment was originally designated as State Highway 3 in 1914. This section of Route 66, like other stretches in eastern New Mexico, generally follows the Ozark Trail that preceded the creation of the Federal highway system in 1926. Coursing across pinyon and juniper covered hills and mesas and crossing small drainages feeding into Bull Canyon and Parajito Creeks, this portion of Route 66 is largely unaltered beyond normal road maintenance. Several ridges permit remarkable panoramas of the interstate, railroad, and Route 66 grades roughly paralleling each other. Each alignment, however, negotiates the topography differently, offering a striking contrast in evolving alignment engineering.

Cuervo to Junction with SR 156

This long abandoned stretch of Route 66 offers unbroken views of scenic vistas of the eastern New Mexico rangeland. Interstate 40 is so well removed to the north that it does not impinge on the historic feel of Route 66. This part of the Mother Road that leads from Cuervo to State Road 156 consists of 6.9 miles built as part of the realignment during 1932. It marks one of the few places where the road deviated substantially from the railroad right-of-way. Even though the years of neglect have led to the erosion of most of the asphalt surface, concrete culverts, modest bank cuts, and fence lines marking the right-of-way still remain, giving the atmosphere an almost reverent feel, as though an old Chevy pickup might come skidding to a stop at the gas station pump. Passing southwest from Cuervo, this portion of Route 66 crosses a deep arroyo carved out by Cuervito Creek. It then climbs 200 feet to an elevation of 5,100 feet at Mesita Contadero. Built on the mesa’s relatively flat rock and caliche surface here, the roadbed stretches to 24 feet wide in some places. Typical of most ascents along Route 66, a yellow median stripe in the road and a gas station awaited motorists at the rise, a spot now marked only by the building’s foundation and concrete pump. The road segment served as Routes 66 and 54 until 1952, when the highway was realigned to its present course following Interstate 40. This segment still serves as a local road.

Albuquerque to Rio Puerco

This 8.5-mile section is marked by a scenic descent from Nine Mile Hill into the Rio Puerco Valley and a through-truss bridge across the steeply eroded banks of the Rio Puerco. At the segment’s eastern end at Nine Mile Hill, the summit offers notable scenery. Eastward lies the emerald chain marking the middle Rio Grande Valley, with Albuquerque stretching across the valley to the Sandia Mountains beyond. To the west is the Rio Puerco Valley with Mount Taylor, rising above to 12,000 feet. Many travelers who drove the Mother Road during the historic period fondly recall the vistas at Nine Mile Hill, especially the views of Mount Taylor and Albuquerque at night, as some of the most inspiring in the American West. Crossing the Rio Puerco is a Parker through-truss bridge with its original bridge plates affixed to the headwalls of the reinforced concrete approaches. Although this portion of the highway was not paved and officially designated as Route 66 until 1937, it was included as mileage in the State’s Federal aid projects in 1932, anticipating its inclusion as a part of Route 66. Federal funding was then used to construct the Rio Puerco Bridge in 1933.

Laguna to McCarty’s

This 17.7-mile road section passes through both Laguna and Acoma tribal lands, gradually ascending into the Rio San Jose Valley through the Route 66 Rural Historic District, which encompasses approximately 216 acres and seven buildings. The sandstone cliffs of Paraje Mesa to the north and red willows lining the Rio San Jose to the south present a rich Southwestern landscape. The seven buildings at the two roadside trading posts offered several roadside services including gas, food, lodging, towing, and auto repairs. The Budville Trading Post (1938) and Villa de Cubero (1936) are two of the best remaining examples of early-roadside architecture catering to passing motorists. Both trading posts have one-story stucco-coated buildings embracing characteristics of the Southwest Vernacular and Mediterranean styles. In varying scales, both indicate the spatial organization of 1930s rural roadside businesses with their long gravel parking lots paralleling the road and their gasoline pump islands at the center of the parking area in front of each trading post. This road segment offers much evidence of early transportation as it crosses over the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railway tracks as well as traces of the old State Road 6 that predated Route 66. The dominant vista along this segment is Mount Taylor, with its often snow-covered conical summit rising to 12,000 feet.

McCarty’s to Grants

Passing through several miles of lava flow, known locally as malpais, this 12.5-mile road section presented a challenge to early road builders during the Depression. During the 1930s, numerous New Deal projects improved this portion of Route 66. A grade separation was added at Horace in 1934, and the entire road section was paved in 1935-36, when a pony truss bridge and a concrete subway were also constructed near McCarty’s. The alignment served as Route 66 until Interstate 40 replaced it after 1956. This road segment’s alignment approximates the drainage of the Rio San Jose and the tracks of the former AT&SF Railway. With Mount Taylor rising over 12,000 feet to the north and the Zuni Mountains to the west, the terrain suggests the rugged Southwest, especially where the road weaves its way through the malpais.

Milan to Continental Divide

This 31.4-mile segment was designated as State Highway 6 in 1914 and a part of the National Old Trails Highway, a trans-regional road association that preceded the creation of the Federal highway system in 1926. The road’s climb out of the Rio San Jose drainage toward Continental Divide takes motorists out of an area that was known for its irrigated agriculture, especially carrots, in the 1940s. The discovery of uranium and development of nearby mines in the 1950s is evident in distant tailing piles and settling ponds near Bluewater. As the road begins to climb toward the Continental Divide, the highest point on Route 66 with an elevation of 7,263 feet, pastures give way to a pinyon and juniper landscape with Navajo homesteads, trading posts, and other businesses periodically lining the roadside. From Prewitt westward, Entrada sandstone cliffs parallel the road to the north, offering a stretch of spectacular unbroken red sandstone extending to the Arizona border. This roadbed remained gravel until the 1930s, when Federal funding resulted in projects to realign and pave the highway. Among these improvements was the elimination of two grade crossings by realigning the highway entirely south of the AT&SF Railway line. As a result, Thoreau and other villages, which prospered with roadside commerce in the 1920s, saw businesses disappear or relocate in the late 1930s, when Route 66 no longer passed along the towns’ main streets.

Iyanbito to Rehobeth

This 9.4-mile segment passes through the broad valley of the Rio Puerco of the West, as it descends from the Continental Divide a few miles to the east. Notable for westbound motorists on Route 66 were the striking red Entrada sandstone cliffs to the north forming an unbroken wall and the increasing evidence of Navajo homesteads lining the road. This roadside geology and cultural landscape served to reinforce the Town of Gallup’s efforts to promote itself as the heart of Indian country, which was part of the attraction of automobile traffic along the Mother Road in New Mexico. The segment was designated State Highway 6 in 1914 and a part of the National Old Trails Highway, a trans-regional road association that preceded the creation of the federal highway system in 1926. During the 1930s the road section was improved and finally paved in 1937. Several concrete box culverts dating to the paving of the road in the 1930s mark small arroyos. This portion served as part of Route 66 until Interstate 40 replaced it after 1956.

|

Glenrico to San Jon, NM: The road diverges from I-40 at Glenrio, passing almost two miles to the south of the interstate through Trujillo and San Jon Creek drainages remaining at about 3,850 feet with little elevation change throughout the road section. Take exit 0 from I-40 into Glenrio. Follow the Route 66 dirt road past where the pavement dead-ends west of Glenrio.

San Jon to Tucumcari, NM: Take exit 356 from I-40 into San Jon. From San Jon, follow the south Frontage Rd. past exits 343 and 339. At exit 335, cross under the interstate and curve with BL 40-Tucumcari Blvd. through Tucumcari. On the west side, rejoin I-40 at exit 329.

Palomas to Montoya, NM: Take I-40 exit 321 (Palomas) across the interstate. Go south to the Frontage Rd. and turn right. Continue ahead on the S. Frontage Rd. past the next overpass (no exit). Slow to curve sharply under I-40, and then continue on the N. Frontage Rd. through Montoya. This segment serves as a frontage road for local traffic. The three bridges are located, 6, 7.2, and 8 miles west of the eastern end of the road section. As the road approaches Montoya, it diverges from its close parallel with I-40, passing a series of small roadside businesses, now vacant and some deteriorating, as well as Montoya cemetery.

Montoya to Cuervo, NM: This section of State maintained Route 66 serves as a frontage and local road along I-40 from west of the Montoya interchange to where the road junctions with the westbound exit ramp at the Cuervo interchange. At I-40 exit 311, cross over I-40 and follow the S. Frontage Road. Cross I-40 again (no exit) and continue along the railroad through Newkirk to Cuervo. Join I-40 at exit 291. Heading west from Montoya, at 7.1 miles, an overpass carries the road into a hilly area punctuated by sandstone outcroppings. At mile 12 the road passes through Newkirk, a rural village with several vacant garages, tourist courts, and cafés that once served Route 66 travelers. West of Newkirk, Route 66 resumes its close parallel with I-40.

Cuervo to NM 156, NM: As a warning, this road is very rough with many washouts and potholes. High clearance vehicles are recommended. This segment serves as a local road for ranchers and utility company line crews. It passes southwest from Cuervo and crosses Cuervito Creek before ascending Mesita Contadero. From I-40, take exit 291 to State Rd. 156. Head west on 156 toward Santa Rosa.

Albuquerque to Rio Puerco, NM: This road segment serves as a frontage road along I-40 west of Albuquerque. It climbs Nine Mile Hill from Albuquerque and Middle Rio Grande Valley before descending into the Rio Puerco Valley. Along Central Ave. in Albuquerque, head west and cross over I-40 at exit 149. Take a left onto the frontage road on the northern side of the interstate. The segment ends at I-40 exit 140, marked by the Rio Puerco Bridge.

Laguna to McCarty's, NM: The eastern half of the section is a local road connecting a series of Laguna tribal villages. The eastern most half-mile portion of the road is four lanes with a slight concrete median, a section completed in 1951 to alleviate congestion around the Pueblo of Old Laguna. West of the Pueblo, this segment returns to a 24 ft. wide two-lane road, containing numerous culverts over the arroyos and drainages descending from Paraje Mesa. The western half of the road passes through several small towns bordering the Laguna and Acoma tribal lands. As the road moves west beyond Budville and San Fidel, numerous drainages from the mountain’s southern slopes account for five multi-box concrete culverts. From I-40 exit 117 (Mesita), take the East-side Frontage Rd. toward Laguna. Follow the curves away from I-40, and around “Dead Man’s Curve.” Approaching town, follow the sharp left turn, then turn right onto Highway 124 through Laguna. Stay with Highway 124 across the railroad, past New Laguna, Paraje, and Budville then through Villa Cubero. Continue on Highway 124 through San Fidel. Cross over I-40 at exit 96; stay with Highway 124 on the south side to McCarty's.

McCarty's to Grants, NM: This section serves as a frontage road along I-40 from west of the McCarty’s overpass at I-40 to the junction of I-40 and NM 117 and then as a local road from that junction westward to where it intersects Business 40 at the east end of Grants. The eastern portion of the section measuring 7.3 miles is designated NM 124, and the western portion, measuring 5.2 miles, is designated NM 117. At McCarty’s a concrete and steel subway (1936) eliminates a grade crossing. One mile west, a steel pony truss bridge bearing 1936 bridge plates cross the Rio San Jose. After the road completes a deviation of approximately one-quarter mile to pass under I-40, it resumes its historic alignment as it diverges from I-40 and passes over a wood grade separation (1934) before reaching the eastern edge of Grants.

Milan to Continental Divide, NM: This road segment is now designated NM 122 and serves as a frontage road along I-40 from west of Milan to the Continental Divide. The eastern 8.6 mile stretch is a divided four-lane road completed in 1951 when several sections of Route 66 in New Mexico were widened. The remaining 22.6 miles is a two-lane road, often closely paralleling I-40 and the tracks of the former AT&SF Railway as it climbs toward the Continental Divide.

Iyanbito to Rehobeth, NM: This road segment serves as a frontage road along I-40. The east end of the segment lies at the junction of Route 66 and the westbound exit ramp of I-40 at the Iyanbito interchange. The segment ends at the State Police station at Rehobeth one-half mile east of the junction of Route 66 and I-40, as the highway widens to four lanes and enters the Gallup commercial strip.

Manuelito, NM to the Arizona Border: This segment is now designated as State Road 118 and serves local residents. It follows the upper contours of the Rio Puerco of the west floodplain, crossing the AT&SF tracks three miles east of Manuelito and then paralleling them to the Arizona border. Take I-40 exit 8 toward Manuelito on SR 118.

For additional information on driving Route 66 in New Mexico, visit the

New Mexico Route 66 Association website.

Laguna to McCarty's

National Park Service

Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program

Glenrico to San Jon

1920's timber bridge

National Park Service

Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program

Montoya to Cuervo

National Park Service

Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program

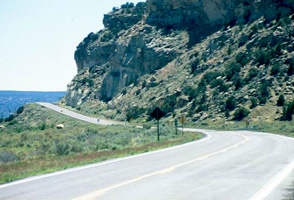

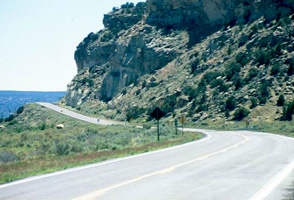

Devil's Cliff near the Arizona Border

National Park Service

Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program

|